Streaming data analysis is a small world, and it can sometimes lead to minor skirmishes over methodology and how results are interpreted. There aren’t many of us, and in the U.S., one of the main analysts in the field is The Entertainment Strategy Guy. I’ll admit, I have some issues with the way he interprets the same data I have access to, particularly with his methodology but that’s what’s fun when it comes to data analysis.

One of his recent posts, which was later picked up by several other media outlets, is based on this chart:

It was published in this article (behind a paywall that I could not read) but his conclusion, based on the composition of the Nielsen Top 10s over several years and the origin of the titles’ streaming services, is clear-cut: the streaming wars are getting more competitive than ever, because Netflix titles now occupy only 50% of the Nielsen Top 10 spots, compared to 80% in 2021.

That sure is one catchy headline but if I may, here are four reasons why it may not be the case after all.

Some streaming services were not covered by Nielsen in 2021 or 2022.

Wondering why HBO Max, Paramount+, or Peacock didn’t have any titles in the weekly Top 10s in 2021 or even 2022? That’s because Nielsen didn’t have permission to include data from those services during that time. HBO Max was only added in July 2022, Peacock in November 2022, and Paramount+ in March 2023. So it’s not that these services finally broke into the Top 10 in 2024 and 2025 after years of trying because they suddenly became more competitive. It’s just that Nielsen couldn’t publish their viewing numbers before.

For instance, I strongly believe that if HBO Max had allowed Nielsen to include its viewing data back in 2021, most of the films from the notorious PopCorn Project (when Jason Kilar released Warner’s entire theatrical slate day-and-date on HBO Max, like Godzilla vs Kong, Mortal Kombat, The Matrix Resurrections etc.) would likely have appeared in the Nielsen Top 10s, pushing some Netflix titles out of them. So in 2021 and most of 2022, Netflix’s share of its presence in Nielsen’s Top 10 was artificially high by some margin.

Netflix does not release anywhere near the number of titles it used to do in order to flood the weekly Top 10s.

To populate 80% of the 52 weekly Nielsen Top 10 over a year, you need to have enough fresh releases to do so and in 2021 up to 2022, Netflix had way more releases than now.

For U.S. series (which make up the majority of Netflix titles in the Top 10 series), Netflix now releases nearly half as many as it did 3–4 years ago.

For films, it’s the same story, with far fewer titles in 2024 or 2025 (so far) than in 2021.

The drop in Netflix’s share of titles in the Nielsen Top 10s doesn’t automatically mean other services are getting stronger. Instead, it mostly reflects that Netflix is releasing fewer titles than before, no longer enough to consistently fill eight or more spots in each week’s Top 10.

Not yet subscribed? Find out why over 1,900 audiovisual industry professionals, journalists, and enthusiasts are already subscribed to Netflix & Chiffres! Subscribe and receive every Wednesday a global overview of Netflix audiences straight to your inbox, and every Saturday a streaming audience snapshot from all U.S. services.

Free. No ads. No strings attached.

The evolution of the Nielsen’s Gauge paints a different picture of the streaming wars in the US.

More surprising, although non-Netflix titles have taken up a larger share of the Nielsen Top 10s, this hasn’t translated into increased TV market share for those other streaming services. Every month, Nielsen’s Gauge gives us a snapshot of these market shares. The latest data from June 2025 shows that Netflix still leads with 8.3% of U.S. TV viewing, outpacing Disney, Prime Video, and the rest.

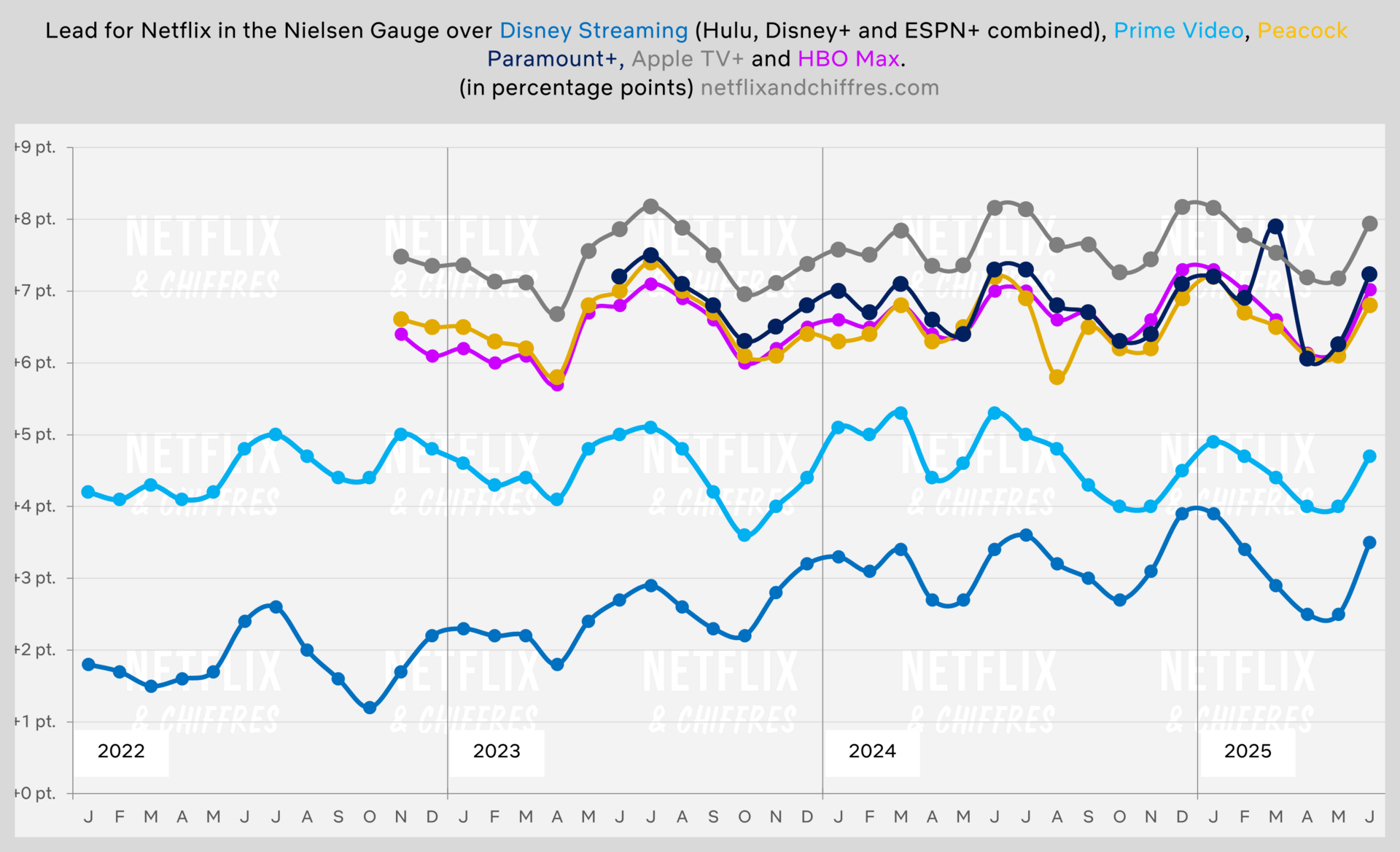

To better visualize the gaps between services and how they’ve evolved over the years, here’s another visualization that shows the monthly change in Netflix’s lead over the other streamers in Nielsen’s Gauge. The higher the lines, the bigger the lead of Netflix over the streamer in question.

For instance, we can clearly see that Netflix’s lead over Disney’s streaming services has widened since 2022. In January 2022, Disney+ and Hulu combined were just 1.8 points behind Netflix in terms of TV market share in the U.S., but that gap had grown to 3.5 points by June 2025. The gap in usage has also increased with HBO Max and Peacock. It's been more stable with Amazon Prime Video and Paramount+, but in practice, no other streamer has meaningfully closed the gap with Netflix since 2022 — despite their visibly increased presence in the weekly Top 10s, Netflix’s pullback in U.S. releases and everything its competitors have been trying to do to catch up (add sports, news, live channels, change names, combine services, you name it.).

If we look at the average yearly gap in Nielsen’s Gauge between Netflix and the other services, again, it’s hard to argue that the streaming wars are getting that much competitive — in either direction.

It’s more like trench warfare as the current gaps (with the exception of Disney) are roughly the same as they were in 2023.

Some services already conceded defeat in the streaming wars.

Finally, the most straightforward argument comes from the streaming companies themselves. Disney and Warner Bros. Discovery have openly admitted that the streaming battle is essentially over for them. Streaming is no longer a top priority in their strategies. They’re content to settle as the third or fourth players behind Netflix and others. Both are cutting back on the number of releases or focusing more on their premium brands at the expense of broader, general-audience content (like HBO Max). It’s hard to imagine anyone at Disney or WBD headquarters believing that the streaming wars are getting more competitive or that they’re empowered to do everything they can to close the gap with Netflix in any shape or form.

In other words, I don’t really agree with the Entertainment Strategy Guy when he concludes that the streaming wars are getting more competitive. It is, in reality, a collective slowdown: a broad, almost synchronized pullback by nearly all major players, and that’s remarkable in itself. The streaming wars may still resemble a cold war or a prolonged war of trenches but more competitive than they were three or four years ago? The data just doesn’t support that, unless you cherry-pick a narrow, flawed and anecdotal angle that happens to make for a clickable headline.

If you liked this article, why not share it with someone who might be interested too?

You can find me here: